MADness

One of my favourite reads in my teens and 20s was MAD magazine. It was quite humorous, and took the rise out of just about everything, but in a gentle way, in contrast to the vituperative stuff that passes for satire these days.

“Gaines cover, Mad Magazine, NYC, NY.JPG“ by gruntzooki is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

For example, I saw the film The French Connection, and found parts of it quite hard to follow. As one does, I assumed the problem was me. Therefore I felt quite vindicated when MAD published a spoof of it called “What’s The Connection?”.

There were many regular features I turned to in each issue, one of them being Scenes We’d LIke To See. In one of these the writers came up with the idea of building adverts and lessons into TV programmes and films.

For example, the war movie:

Sergeant: OK, boys, let’s go.

Private: I can’t, Sarge. My stomach is killing me.

Sergeant: Stomach ache is caused by a build-up of acid. What you need is Pepticide. Pepticide has been developed by leading scientists to fight gastric acid fast. Here, take one.

<A short while later>

Private: I feel so much better now, Sarge.

Sergeant: That’s because Pepticide works fast, soldier. Now let’s get them dirty reds.

Another example: the Western.

Boy: Thank you, Sheriff, for killing Big Jake. Now we can all sleep easily in our beds.

Sheriff: I didn’t kill him, Son. What happened was that when I pulled the trigger, it released the hammer. Then the compressed spring drove the hammer forward. The firing pin on the hammer then extended through the body of the gun and hit the primer. The primer exploded, igniting the propellant. The propellant burned, releasing a large volume of gas. The gas pressure drove the bullet down the barrel. The gas pressure also caused the cartridge case to expand, temporarily sealing the breech. All of the expanding gas pushed forward rather than backward, causing the bullet to fly out1.

Boy: So thanks to heat and expanding gases, Dodgeville is now free of Big Jake?

Sheriff: Yep. That and the fact that I outdrew him.

All very chortlesome, but these days that sort of lecturing is a regular feature of TV programmes — at least in England. For example, I recently watched a series called Sherwood, which is a murder mystery that takes place against the miners’ strike in the 1980s. The situation affecting communities was very well depicted, but then in the final episode the programme makers couldn’t resist shoehorning in a lecture. In fact, not one lecture but two.

They weren’t flagged up as lectures, of course. They took the form of a couple of people speaking out in a meeting in a village hall, but that made it worse in a way. Perhaps it would have been better to have had a voiceover telling us what we were supposed to think and feel — at least that would have been more honest.

Thiis kind of thing reminds me of the Radio <country> I sometimes listened to in my youth. Quite often a man and a woman were having what was meant to sound like a genuine conversation, which invariably went like this:

Man: Well, Miranda, I’m so excited. The production of steel ingots has risen by over 50% since the last quarter.

Woman: That’s nothing, Darren. The production of chocolate has gone up by 200%.

etc

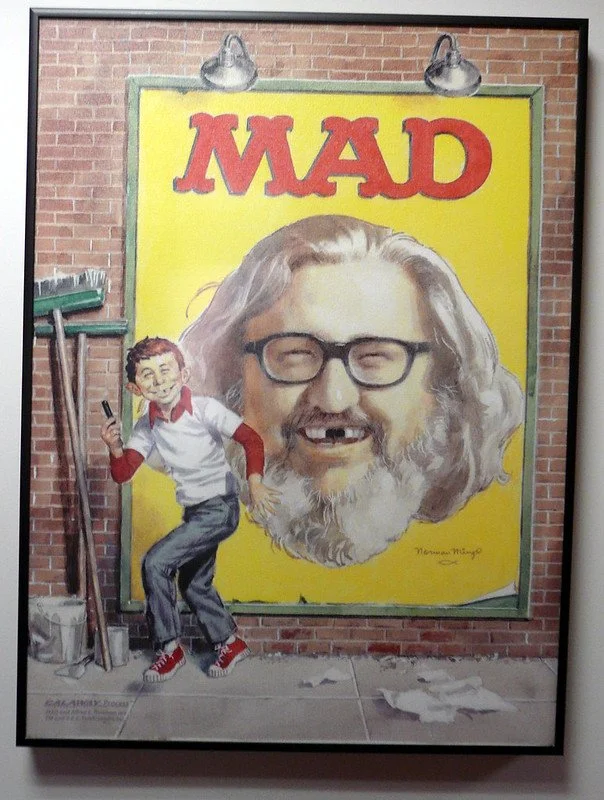

In other words, this is not a modern phenomenon. Indeed, when I was on a short holiday recently I bought a copy of a girl’s magazine called Mandy, which I somehow missed out on in my youth. In fact, I bought it for the sole purpose of illustrating this article because Mandy, back in 1977, seemed to be a real goody two-shoes who says things like “What a lot of litter there is, but we’re helping to clear it up.”. Another story ends with the girl saying something like “There’s nothing as important as friends and family.”

cover of Mandy

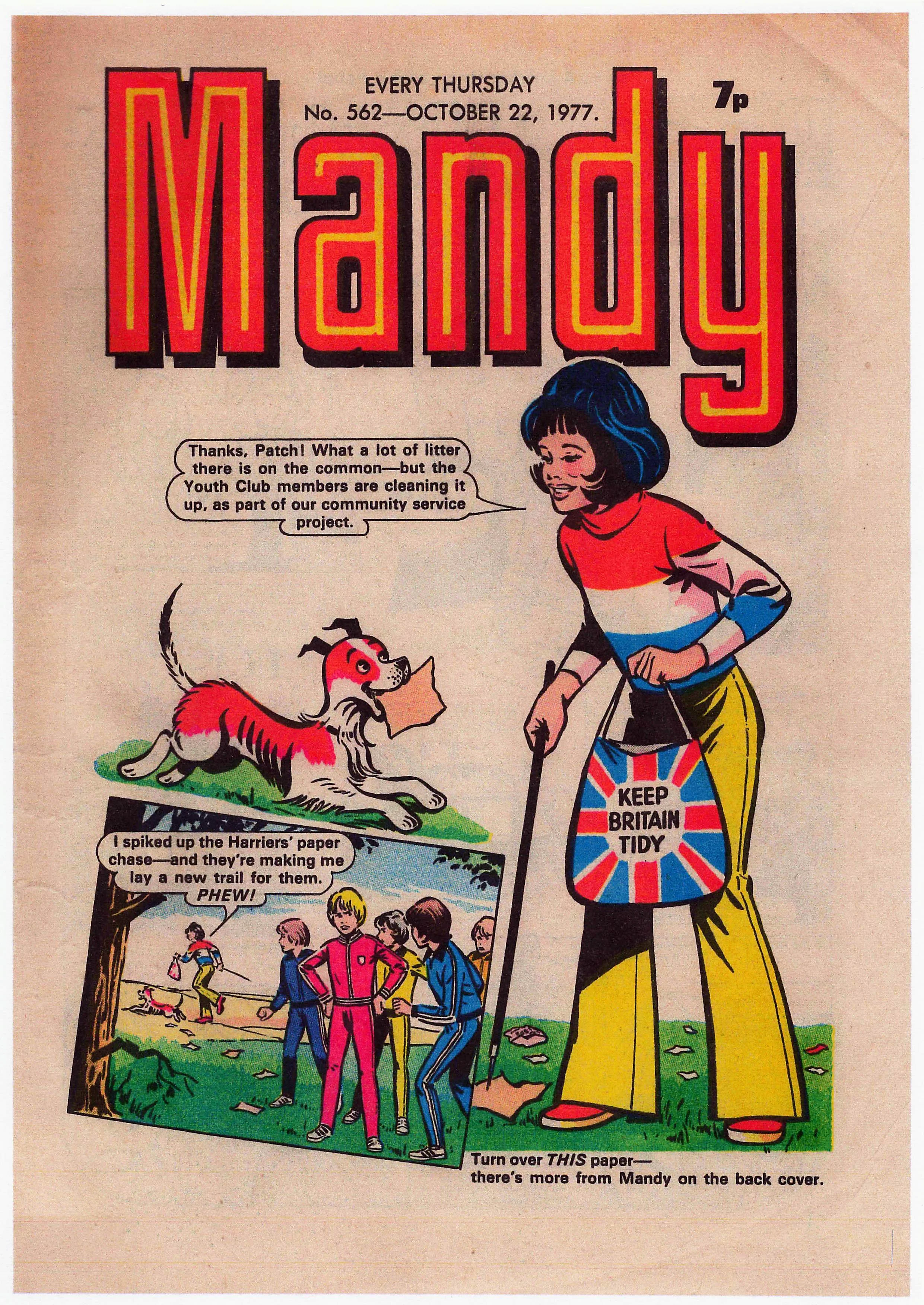

I mean, this was propaganda, and not even that convincing. I preferred girls who had a bit of the rebel about them, like Anne (see She Really Got Me) or Minnie the Minx in the Beano:

Minnie the Minx

But it just goes to show: clumsy sermonising has been with us for a very long time.

This article first appeared in Eclecticism.Click that link to comment and to read others’ comments.